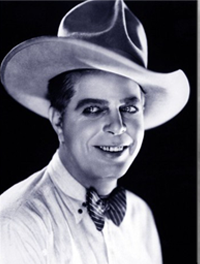

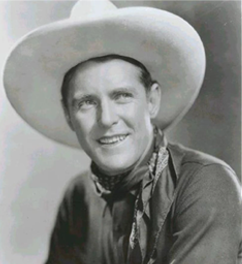

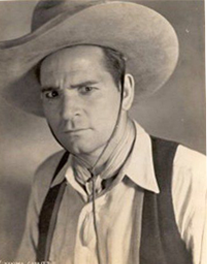

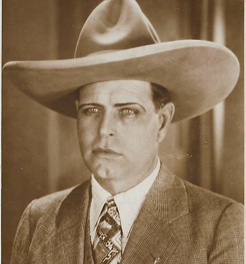

Cowboys of the Old West populated early Westerns

The first cowboy movies – short and silent — starred a posse-full of real cowboys. As with all movies, there was some embellishment.

The Western, an enduring staple of motion pictures, first developed myths stacked upon previous myths of the Old West, and it all came together like alchemy around 1900, just as the real time was ending.

When was the real Old West? In one sense it is an imaginary time. If the historical window is narrowed to the time most favored by the movies, the significant Old West occurred between the end of the Civil War, 1865, and the turn of the century. That is a scant 35 years.

Where was the real old West? It was a geographic phenomenon. It centered around such places as California and the gold rush, similar precious metal runs in the Dakotas, Montana, Colorado and Wyoming, post-Civil War cattle drives in Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona and Kansas, and the resulting range wars in Central Texas, the Texas Panhandle, and the foothills of central and northern New Mexico.

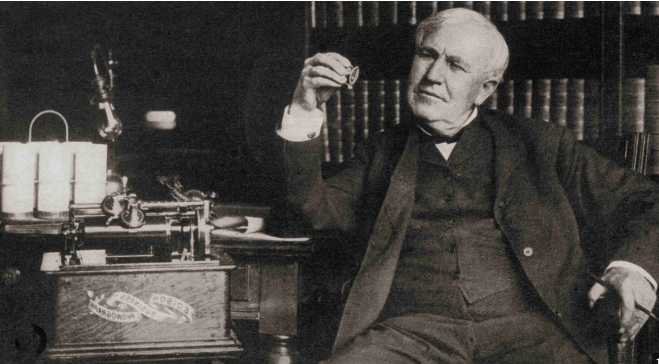

When were movies invented? In 1888, midway through this imaginary time, Thomas Edison conceived of a motion picture camera (the Kinetograph) and a peep-hole viewer (the Kinetoscope). These innovations created a unique confluence, when the last vestiges of a passing curiosity, anomaly, phenomenon – the Old West — could be recorded for all time.

It was as if the camera was invented just before the meteor fell that destroyed the dinosaurs

By 1900, Western silent films were short — mostly a few minutes in length — and featured scenes of cattle roundups or staged incidents like stagecoach robberies or fights with Indians. The camera did not exist when these events occurred, so film makers were challenged to recreate them for a modern audience. The myths were duplicated and invariably created an imperfect copy.

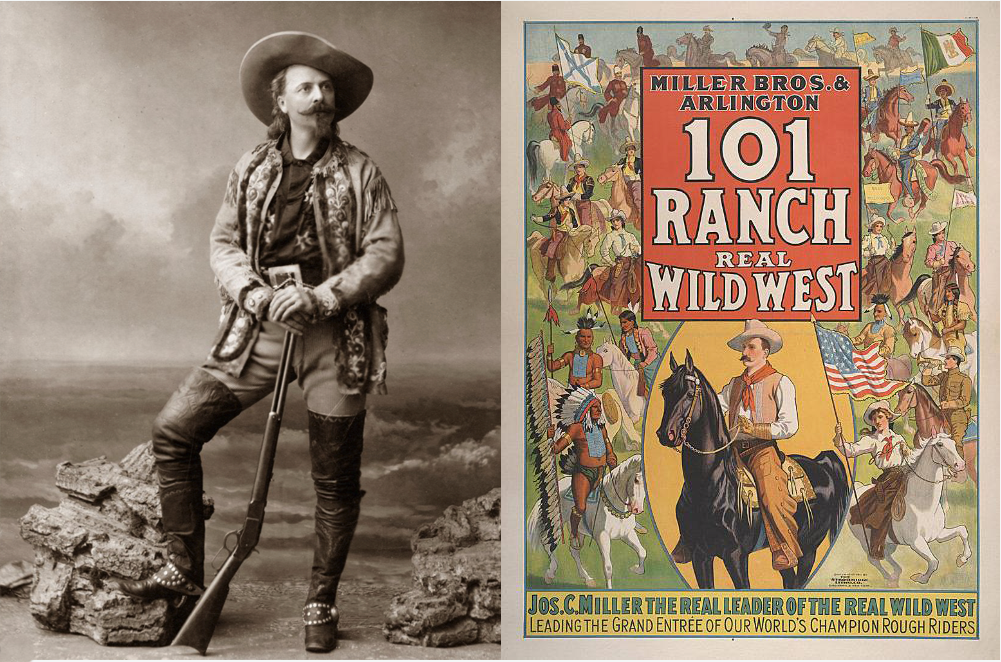

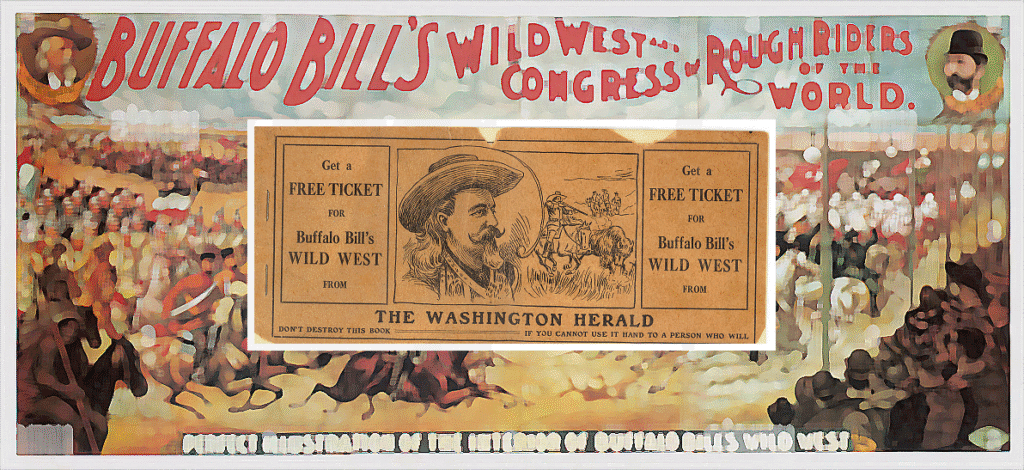

To create the illusion, these early film pioneers needed real cowboys and Indians, and the obvious resource were the multiple Wild West shows traversing the country as live entertainment, exemplified by ‘Buffalo Bill’s Wild West’, founded in 1883 by Buffalo Bill Cody. Another resource was the ‘101 Ranch Real Wild West’, an offshoot of the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch in northern Oklahoma.

William Frederick Cody (1846-1917) was born in Illinois territory, but his family relocated to what would become Kansas when he was young. He was a genuine participant in the real Old West. At age 11, he claimed to have killed an Indian during the Utah War (1857-58), an armed confrontation between the US government and the Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory. In the 1850’s he worked as a freight company horseback courier, escorting wagon trains headed to California for the ’49 gold rush. He enlisted in the Union Army in 1863 after turning age 17 and served as a teamster in the 7th Kansas Calvary.

After the war, he joined his friend Wild Bill Hickock in Junction City, Kansas as an Army scout, then served as a buffalo hunter, supplying meat for railroad construction workers, where he picked up the nickname Buffalo Bill. He returned to his role as US Army scout in 1868 and was named Chief of Scouts for the 5th Cavalry Regiment and later for the Third Cavalry during its Plains Wars campaigns. These conflicts, stretching from 1865-1898, resulted in almost 1,000 military casualties and an untold number of native Indian deaths, men, women and children. An entire culture was almost eliminated.

Cody experienced the harsh reality of the Old West, and he seemed to enjoy telling his tales. He would soon participate in a more romanticized version courtesy of writers like Ned Buntline, who met a 23-year-old William Cody in 1869. Buntline embellished Bill’s stories in an early dime novel called “Buffalo Bill, King of the Bordermen,” first serialized in the Chicago Tribune. Other stories followed. In 1872, Cody was on stage and touring in “The Scouts of the Prairie.” one of the original Wild West shows produced by Buntline.

By 1883, after more stage appearances for others, Cody founded his own “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” The formula was simple: stage the events written about and include some of the real people who had been there, the most famous including Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickock, Sitting Bull and Calamity Jane.

The melding of these two phenomena – the Wild West show and the motion picture — occurred in 1894, when Edison studios filmed Buffalo Bill and his large company and some of his featured acts, including sharpshooter Annie Oakley and her husband Frank E. Butler.

Other Wild West shows, and there were many, soon joined the mix. Among the most notable was the Miller Brothers’ traveling 101 Ranch Wild West Show which originated in post-Civil War Oklahoma Territory. Many of the Western stars who performed in the first half of the 1900s got their start or were associated with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, a business enterprise that encompassed four counties. These included Will Rodgers, Tom Mix, Hoot Gibson, Buck Jones, Yakima Canutt, Bill Pickett and Art Acord. Buffalo Bill himself was associated with the Miller Ranch after his own enterprise ended. These early days are profiled by Michael Wallis in his well-written history “The Real Wild West: The 101 Ranch and the Creation of the American West,” published by St. Martin’s Griffin (New York, 1999).

Both Wild West shows and the movies would flourish simultaneously until the 1920’s when the inevitable popularity of motion pictures surpassed the now aging troupes of cowboys and Indians trying to recreate the past. Movies then inherited this past, to do with as it pleased.

Edison’s first experiments with depicting the Old West were shorts, often only a few minutes in length. This evolved with The Great Train Robbery (1903), directed by Edwin S. Porter. This film was longer, 12 minutes, and more artistic. Instead of a single long shot, it told its story cinematically with 14 scenes edited together. Considered the first widely seen Western, The Great Train Robbery was shown across the U.S. in vaudeville houses since there were no established movie theatres.

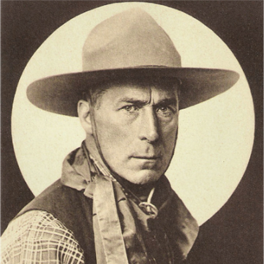

The first Western movie star was Gilbert M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson (1880-1971). He was born Maxwell Henry Aronson, the son of a Jewish dry goods salesman, in Little Rock, Arkansas. He co-founded an early production company, Essanay Studios, and starred in 148 shorts as ‘Broncho Billy Anderson’ beginning in 1908.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Aronson an “Oscar” in 1958 for his contributions to cinema. His only surviving feature film is The Son of a Gun (1918).

The 1910’s also saw the birth of the feature film, running an hour or more. This longer format contributed to the booming construction of movie theatres. The world’s first movie theater exclusively devoted to showing motion pictures was the Nickelodeon, which opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on June 19, 1905. It showed mostly short films which did not exceed the length of a single cannister of film (under 20 minutes). By 1925, there were approximately 25,000 movie theatres in the U.S.

This reflected the expansive growth of the film industry, particularly the advent of full sound in the late 1920’s. It is estimated there were around 22,000 in operation in 1930.

The western star that made the most of the feature film’s longer format was William S. Hart. This began with The Bargain (1914). Hart was born in the East – he wasn’t a real cowboy — but he relocated to California and eventually bought a large ranch that today is a regional park and museum.

After these early beginnings, the so-called “Big Four” of Western cinema were Tom Mix, Hoot Gibson, Buck Jones and Ken Maynard, all with connections to the Miller 101.

Tom Mix started as a ranch hand for the Miller 101 Ranch and later performed in its traveling Wild West show. He made short films with the Selig Polyscope Company in the 1910’s, but he came to the forefront after signing with Fox Films to make features. Only one of Mix’s 1910’s features, Ace High, survives. A few of his Selig one-reelers can still be found, such as Sage Brush Tom (1915), An Arizona Wooing (1915), and Local Color (1916).

Hoot Gibson (1892-1962) was another rodeo champion turned Hollywood cowpoke who appeared in more than 300 films like The Dude Bandit (1933). His association with the Miller 101 began in 1906 as a ranch hand, then he moved on to Wild West shows and the rodeo circuit and was named “Cowboy Champion of the World” at Pendleton, Oregon in 1912. He retired from the movies in the 1950’s.

Buck Jones (1891-1942) worked for various Wild West shows and began as a movie stuntman in 1917. He starred in western serials for Universal Pictures until 1937, bringing a light touch to a string of B-movie Westerns. He signed with Monogram Pictures in 1941 and starred in more cowboy serials, most notably the Rough Riders series. He died tragically in a nightclub fire in 1942.

Ken Maynard (1895-1973) started as a trick rider in Wild West shows and is credited as the first “singing cowboy.” He never worked for the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, but he was a friend of the family. Maynard first starred in the silent film $50,000 Reward (1924). He worked steadily in the movies throughout the twenties and thirties, appearing in such films as Señor Daredevil (1926), The Devil’s Saddle (1927). Branded Men (1931), In Old Santa Fe (1934) and Smoking Guns (1934). He was signed and released by several studios, but his drinking and behavior on set eventually took its toll. He was out of the movies by the 1950’s, and he reportedly died destitute in 1973.

The Miller Brothers 101 Ranch contributed a long list of other real ranch hands that later were featured in the movies. One famous name associated with the ranch was Will Rogers (1879-1935), who never worked for the Miller spread but was closely associated with the family.

Rogers appeared in more than 50 silent films, and he was equally famous as an entertainer and storyteller on radio and stage. There are books filled with Will Rodgers’ quotes, the most famous being “I never met a man I didn’t like.” He died in a plane crash in 1935 after appearing in 71 movies throughout his career: 50 silent films and 21 “talkies.”

There were other real cowboys linked to the Miller 101 and transformed into Hollywood players:

–Yakima Canutt (1895-1986), a former rodeo rider from Washington state whose fearless horsemanship earned him “first stuntman” status. He was expert at falling off horses. He doubled for John Wayne in the movie Stagecoach (1939), performing the “transfer and fall from a galloping horse” stunt, allowing the stagecoach to pass over him. He also doubled for Clark Gable in Gone with the Wind (1937) and helped devise the chariot race scene in Ben Hur (1959).

— Jack Hoxie (1885-1965), who was born in Oklahoma Indian Territory to a Native American mother. He worked for the Miller 101 Ranch and related traveling show and appeared in several popular silent Westerns — Thunderbolt Jack (1920) and The Last Frontier (1926). Hoxie was basically uneducated, so the advent of sound was detrimental to his movie career. The ‘talkies’ sent him back to the Miller Ranch. He returned to Hollywood briefly in the early 1930’s.

–Art Acord (1890-1931), who starred in more than 100 shorts, serials and features from 1910 to 1929. He began as a Miller 101 ranch hand and performed in its Wild West show. He worked for such studios as American, Fox, Universal, and Blue Streak Westerns. His life ended sadly and under suspicious circumstances. After leaving Hollywood, he reportedly was working as a miner in Mexico. He was found dead in a Chihuahua City hotel room, a death variously reported as a suicide — he had taken poison — or a murder. The coroner report said he died of “acute alcoholism.”

–Bill Pickett (1870-1932), who competed in his first rodeo in 1888 and joined the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch and Wild West Show in 1905. He is credited with inventing the rodeo sport called “bulldogging,” where a rider jumps from his horse to grab a steer’s horns and, using his leverage, twists the beast’s neck until it falls to the ground. Pickett added his own personal touch: biting the steer on the lip. He appeared in several early silent pictures, but he starred in only one: The Bulldogger (1923). He would become the first African American cowboy to be inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1972.

There were an estimated 42 silent movie shorts with a cowboy theme made from 1903 until 1910. From 1910 until 1920, there were some 180 Western silent films. The Internet Movie Data Base (IMdb) website profiles its own “20 Greatest Western Stars” here.